Real Integrals

There are a few cases where we can use complex contour integrals to simplify finding real valued integrals.

Full Period Trigonometric Integrals

If we have an integral of the form

$$ I = \int_0^{2 \pi} g(\sin{\theta} \cos{\theta}) d \theta, $$

with a rational function $g$ of $\sin{\theta}$ and $\cos{\theta},$ we can do some magic with a closed contour integral around the unit circle.

We can let $z = e^{i \theta},$ we get

$$ \cos{\theta} = \frac{1}{2}(e^{i \theta} + e^{-i \theta}) = \frac{1}{2} \left ( z + \frac{1}{z} \right ). $$

$$ \sin{\theta} = \frac{1}{2i}(e^{i \theta} - e^{-i \theta}) = \frac{1}{2i} \left ( z - \frac{1}{z} \right ). $$

Additionally,

$$ \frac{dz}{d \theta} = ie^{i \theta}, \quad d \theta = \frac{dz}{iz}, $$

and because our integral ranges from $0$ to $2 \pi,$ the variable $z = e^{i \theta}$ ranges counterclockwise once around the unit circle, so our integral becomes

$$ J = \oint_{|z|} f(z) \frac{dz}{iz}. $$

We then can proceed with a normal contour integral, using residue methods to deal with any singularities enclosed by the contour.

We can use this technique to prove the following theorem

$$ \int_{0}^{2\pi} \frac{a}{\,b - c\sin\theta\,}\,d\theta = \int_{0}^{2\pi} \frac{a}{\,b - c\cos\theta\,}\,d\theta = \frac{2\pi a}{\sqrt{b^{2}-c^{2}}}, \qquad b^{2} > c^{2}. $$

Improper Integrals

This method applies for integrals of the form

$$ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) dx, $$

where $f(x)$ is a @rational-function. It can also be used with integrals of the form

$$ \int_0^{\infty} f(x) dx $$

where $f(x)$ is both @rational and @even.

As an example, let's look at

$$ I = \int_0^{\infty} \frac{1}{1 + x^4} dx = \frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{1 + x^4} dx. \tag{a} $$

We can solve this real integral by looking at the complex contour integral

$$ J = \frac{1}{2} \oint_C \frac{1}{1 + z^4} dz, $$

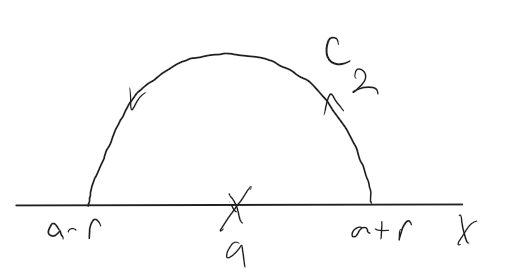

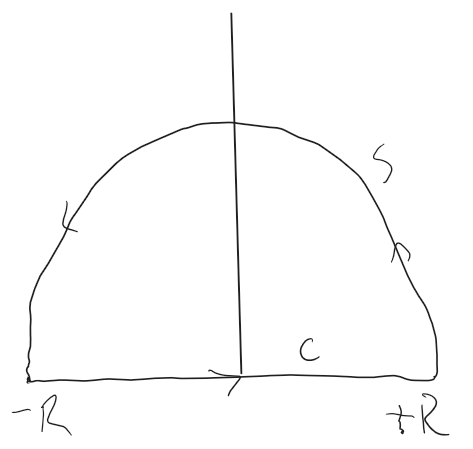

with $C$ being the upper half-circle closed along the $x$-axis:

Here, $C$ is the entire contour, and the part labeled $S$ is the upper half-circle.

The key concept is that if we rewrite (a) as

$$ I = \lim_{R \to \infty} \frac{1}{2} \int_{-R}^{R} \frac{1}{1 + x^4} dx, $$

then the semi-circle grows to enclose the entire upper half-plane. If the value of the complex contour integral along $S$ goes to $0$ as $R$ goes to infinity, then the contour integral is equivalent to the integral along the real axis, and we can use residue methods to compute it, accounting for any singularities in the upper half-plane.

In order for $\oint_S f(z) dz$ to approach $0$ as $R \to \infty,$ a sufficient condition is that the denominator of $f(x)$ has a power of $x$ at least two degrees higher than the numerator, which applies in our case.

Now, $z^4 + 1$ has 4 zeros, but only two of them, $z_1 = e^{i \pi / 4}$ and $z_2 = e^{i 3 \pi / 4}$ occur in our semi-circle (i.e. they are in the upper half plane).

Using the Residue Theorem, we have then that

$$ I = \frac{1}{2} * 2 \pi i * (\Res{z \to z_1}f(z) + \Res{z \to z_2}f(z)) = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{4} \pi. $$

Putting this all together, we have, in general, with the conditions specified,

$$ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) dx = 2 \pi i \sum \Res f(z). $$

Improper Integrals with Simple Poles on the Real Axis

Let's say we have an integral

$$ \int_A^{B} f(x) dx \tag{a} $$

whose integrand becomes infinite at a point $a$ in the interval of integration.

Then, (a) means, by definition

$$ \int_A^{B} f(x) dx = \lim_{\epsilon \to 0} \int_A^{a - \epsilon} f(x) dx + \lim_{\eta \to 0} \int_{a + \eta}^{B} f(x) dx. $$

However, it may be the case that neither limit exists when both $\epsilon$ and $\eta$ approach $0$ independently, but that the limit

$$ \lim_{\epsilon \to 0} \left [ \int_A^{a - \epsilon} f(x) dx + \int_{a + \epsilon}^{B} f(x) dx \right ] $$

does exist.

This limit is called the Cauchy principal value of the integral and is written as

$$ \text{pr. v. } \int_A^{B} f(x) dx. $$

This principal value can exist, although the integral itself is undefined. We can use this for the following theorem in the case there are simple poles on the real axis and we have an integral from $-\infty$ to $\infty.$

Putting this all together, we get, for an integral that has poles off of the real axis and simple poles on the real axis, we get

$$ \text{pr. v. } \int_{- \infty}^{\infty} f(x) dx = 2 \pi i \sum \Res f(z) + \pi i \sum \Res f(z), $$

where the first sum covers all the poles in the upper half-plane and the second over all the poles on the real axis (which must be simple.

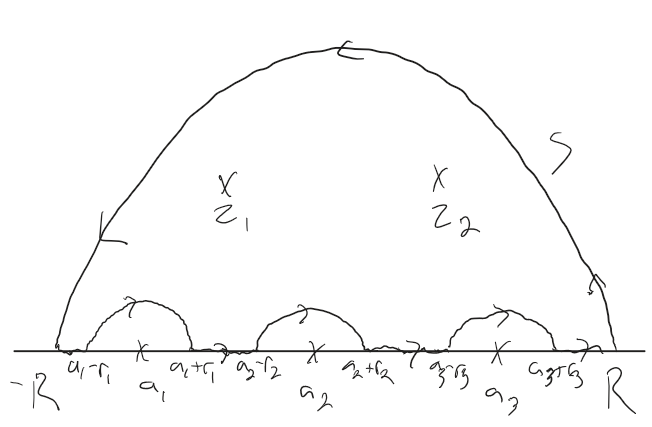

For example, given the situation illustrated below:

we have

$$ \text{pr. v. } \int_{- \infty}^{\infty} f(x) dx = 2 \pi i \left ( \Res_{z \to z_1}f(z) + \Res_{z \to z_2}f(z) \right ) + \pi i \left ( \Res_{z \to a_1}f(z) + \Res_{z \to a_2}f(z) + \Res_{z \to a_3}f(z) \right ). $$